On 8 December 2024, opposition forces seized the Syrian capital Damascus, toppling the regime of President Bashar al-Assad after more than 13 years of civil war. The capture of Damascus marked the end of a surprise offensive led by the Islamist rebel group Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), which saw them break out of their Idlib stronghold and capture nearly all government-held territory in less than two weeks after years of stalemate. The sudden collapse of the Assad regime after more than five decades in power – and the failure of its allies to rescue it – has resulted in further uncertainty over the future of political and security stability in Syria, and what the implications will be for the wider region.

The removal of Assad may prove to be a significant step towards enhancing Syria’s stability in the long term, improving accessibility for organizations focused on the country’s humanitarian and reconstruction needs caused by over a decade of conflict. However, numerous issues are yet to be resolved. Indeed, while Assad has gone, the country is not united, with several opposition groups still in a state of conflict. Related to this, there is concern that terrorists may seek to exploit the current lack of overall security authority to expand their operations. These factors, as well as the actions of global players who continue to act in line with their own foreign policies within Syrian territory, mean that a widespread improvement in the country’s security situation is unlikely in the coming months.

Continued conflict and disunity

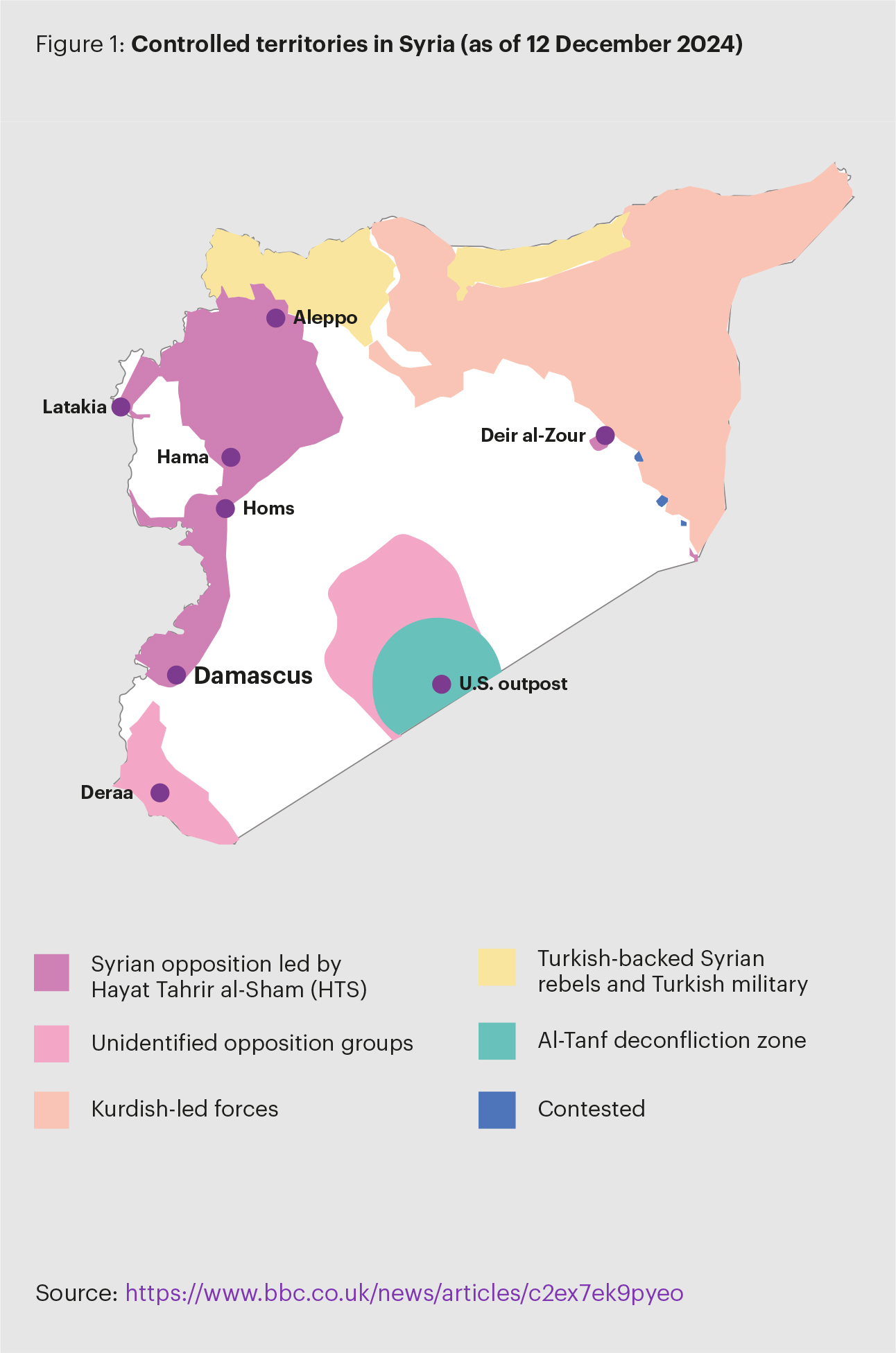

The main phase of the civil war has largely concluded, but conflict persists in parts of Syria. Security conditions are expected to remain fluid, and existing physical and travel security risks are unlikely to improve for at least the next several months. After the fall of Assad’s government, the Syrian military dissolved, and its allies – including Russia and Iran – announced that they would end all combat operations to allow for a peaceful transition of power to the opposition. Despite this, clashes have continued in northern and eastern Syria. In the week since Assad’s ouster, Turkish backed militants have launched offensives against cities and towns in the north held by the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), a collection of mainly Kurdish militias. Turkey continues to oppose the SDF’s presence along its border given the group’s alleged ties to the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), which the Turkish government considers a terror organization.

The conflict between Kurdish and Turkish backed forces is likely to continue in the coming weeks and could endure for longer if a negotiated settlement is not found. Turkey has long sought a demilitarized zone in northern Syria, having previously tried to compel the Assad regime to grant one. With Assad gone, Turkish-backed forces expelled the SDF from areas west of the Euphrates River before agreeing to a U.S.-backed ceasefire that paused its anti-SDF offensive. This agreement is unlikely to hold in the medium term, given Turkey’s longstanding demand for a demilitarized zone and the desire of its largely Arab militias to expel Kurdish forces from Arab majority cities and towns. It is unclear if HTS will become involved in the conflict. While HTS opposes Turkey’s military presence in Syria, it is also apprehensive of the SDF’s current control over Arab-majority areas in the country’s north and east. HTS may try to negotiate a compromise that attempts to accommodate its interests whilst avoiding direct confrontation with either Turkey or the SDF. Israel has also acted militarily in the wake of Assad’s fall. Immediately after opposition forces seized Damascus, Israel carried out hundreds of airstrikes against sensitive military targets across Syria, fearing that rebels could seize sophisticated weaponry. Over several days Israel destroyed much of the country’s air and naval forces, radar and missile defenses, and suspected chemical weapons depots. In addition, Israeli ground forces have invaded the Syrian side of the Golan Heights, seizing strategic positions and several villages to form a demilitarized zone. Israel says it does not seek a permanent military presence in Syria but has expressed concerns that instability in the country could allow armed groups to threaten it; however, it is unlikely that former rebel forces will try to target Israel in the near term. Although the Syrian interim government has condemned Israel’s bombing campaign and ground incursion, it has also stressed that it is not interested in conflict with Israel. HTS and its allies know that they cannot seriously challenge Israel in a war, which would prove costly to Syria in its weakened state. Furthermore, Syrian officials have indicated a willingness to accommodate Israel’s main security concerns, including the presence of Iranian and Hezbollah military forces.

Continued conflict and disunity

Syria’s political transition is complicated by the array of competing political and sectarian interests that need to be accommodated. HTS and its leader Abu Muhammed al-Jolani hold significant influence over the transition process given their role in instigating Assad’s collapse, and their experience governing rebel-held Idlib province over the last five years. That influence is underscored by the installment of Muhammedal-Bashir – the head of HTS’ government in Idlib – as interim prime minister. Bashir says his administration will oversee a transitional period ending 1 March 2025.

Foreign governments and many internal factions in Syria have reservations about HTS, which is designated a terrorist organization by the U.S., the U.K., and others. Prior to establishing HTS, Jolani was a member of al-Qaeda and the Islamic State (IS) in Iraq but broke from the group when it established itself in Syria. Jolani has spent recent years publicly moderating his Islamist beliefs by condemning transnational terrorism, ordering the protection of religious and ethnic minorities in HTS-held territory, and cracking down on IS and al-Qaeda. It is unclear the extent to which Jolani and HTS have truly moderated their beliefs. While initial statements by HTS about the rights of women and religious minorities are promising, more time is needed to accurately gauge their commitment to them. Like the Taliban in Afghanistan, Jolani could seek moderation only to renege after consolidating power. The U.S. and other countries have indicated they are willing to engage constructively with HTS and could rescind the group’s terrorism label if it takes tangible steps toward political and religious pluralism. This could incentivize HTS to commit to political and social moderation, especially if foreign governments make diplomatic recognition and reconstruction aid contingent on reforms.

Stabilizing Syria’s political system will require consensus on several key issues, all of which are potentially fraught. The post-transition government must adequately ensure the protection of Syria’s religious minorities, including Alawites, Christians, and Druze, and limit the threat of reprisals. Transitionalauthorities must also strengthen Syria’s political institutions, designed to keep Assad in power and hollowed out by almost 14 years of conflict. The issue of regional autonomy may also become pivotal given the de facto independence that Syrian Kurds attained during the war. A failure to adequately address these or other issues could quickly cause conflict between rival armed groups to flare again.

Stability also depends on the demobilization of Syria’s various rebel groups and the reintegration of their members into a military under the unified command of the government. Past experiences in Lebanon, where Hezbollah’s armed wing was allowed to remain outside of state authority, have shown the political and security risks in countries that lack a state monopoly on the use of force. Syria is likely to rely heavily on HTS and other militant groups for security in the near to medium term after Israel destroyed much of what remained of the Assad regime’s military assets. This is largely unavoidable for now, but allowing armed groups to maintain independence can lead them to align with specific political leaders, institutions, and foreign governments – as is the case in Libya. When disputes arise, they are often quick to devolve into violence, with each armed faction vying for their preferred political outcome.

Implications

Developments in Syria will have broad implications for the Middle East. In the immediate term, Assad’s ouster is a significant setback for Iran, which benefits its staunch enemy Israel. Iran used Syria to project its power across the Levant region and support proxies, enabling it to deter Israeli military aggression. Iran has now lost all its military bases in Syria and the land routes it used to transfer weapons and military equipment to Hezbollah in Lebanon, complicating efforts to resupply and revitalize the militant group after its long and costly conflict with Israel. Iran’s “axis of resistance” was the cornerstone of its deterrence strategy in the region and the erosion of its capabilities in Lebanon and Syria has resulted in a significant strategic imbalance in its rivalry with Israel.

Despite recently agreeing to increased international monitoring of its nuclear enrichment activities, Iran, increasingly isolated, could see restoring deterrence through developing nuclear weapons as its best option to guarantee the long-term survival of the regime. It is also possible that Israel will come to the same conclusion, with current conditions – notably a significantly weakened Hezbollah and the destruction of former Assad-regime air-defense systems – potentially being perceived by Israel as presenting a narrow window of opportunity to decisively strike Iran. Due to these factors, a substantial strike against Iran’s regime or nuclear facilities cannot be ruled out in the coming months, if Israel can overcome some of its remaining logistical and capability gaps. While recent precedent has suggested that little support would be offered by Tehran’s allies to counter Israeli offensive actions, Iran and its remaining proxies such as the Houthis would likely respond with disruptive attacks, including against Israel and key maritime chokepoints.

In terms of political stability in the region, Assad’s overthrow, closely following Israel’s elimination of much of Hezbollah’s leadership, further undermines the perception that Iran has the ability to protect its allies in the region. This could have implications for Lebanon, Iraq, and Yemen in particular, where Iranian supported groups wield significant political influence, often backed by force. Anecdotal reporting indicates that opposition groups in Iran are hopeful that Assad’s downfall will inspire further internal resistance against the Iranian regime. Given recent bouts of significant unrest in Iran, this is a possibility, although activists and opposition groups in Iran remain disorganized following the regime’s crackdown after the 2022 uprising. Lebanon may also have an opportunity to shift the domestic political landscape and elect a new president, by negotiating with a presently more amicable Hezbollah. While there is currently little sign of unrest developing along these lines, citizens could seek to pressure their governments to reduce Iranian influence.

In addition to potentially representing the start of a new phase in the conflict between Israel and Iran, the rapid collapse of the Syrian government has raised concerns about a possible IS resurgence. Although weakened after its territorial defeat, IS cells have remained active across central Syria’s remote desert and have sharply escalated the frequency of their attacks over the last year. The Syrian military collapsed quickly in central Syria as rebels advanced on Damascus, leaving little formal security presence in areas with active IS cells. Underscoring concern held that IS could use the chaos of the regime’s collapse to consolidate power, the U.S. carried out dozens of airstrikes against the group in central Syria in the hours after Assad fell – including targeted strikes on militant gatherings.

While IS is unlikely to pose a transnational threat in the near term, a failure to fill the security vacuum left in central Syria could let the group strengthen further over time, while fighting between groups such as the SNA and SDF could distract them from their mutual aim of countering IS in the north. Should the threat posed by IS increase, the group’s most likely target beyond Syria would be Iraq. However, a relative lack of support in areas under its control compared to when the group was at its peak, means that any attacks would likely be small in scale.

In Europe, there is likely to be an increased push by some governments to repatriate Syrian refugees or otherwise limit asylum applications given the fraught politics around immigration across the continent. In the days after Assad’s fall, multiple countries paused or suspended asylum applications for Syrian nationals – including Austria, Croatia, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, the U.K., and others. Austria and Denmark have gone further, calling on Syrian refugees in their countries to return to Syria. Other governments and populist, anti-immigration parties could bolster calls to repatriate Syrian refugees now that Assad is gone – despite evidence that the country is still unsafe. Tensions over refugee repatriation could cause protests and anti-government demonstrations in countries with large Syrian refugee communities, such as Germany, Sweden, and the Netherlands. The issue is likely to be particularly salient in Germany’s upcoming federal election in February 2025, in which the anti-immigration Alternative for Germany (AfD) is expected to perform well.